All (climate) COPs Are B*stards

On the need to "Defund the COPs"

The ACAB slogan has always jarred with me somewhat.

I understand (and respect) it as a systemic critique, intended to reveal that it's impossible for any individual, no matter how genuinely committed to justice they are, to truly contribute to a just world from within a system so deeply unjust as policing. A system that is structurally designed to enforce, through violence and the threat of violence, the power of the state, the property of the wealthy, and the divides of class and race and gender, cannot be used effectively to challenge those injustices. Yes, as an individual within it, you might be able to do some specific good, reduce some specific harm, but... the master's tools and all.

And yet, ACAB makes that critique through a personal attack that seems only likely to heighten tensions and deepen divides. Our fight is systemic, not (usually) with individual cops and their families. Indeed, a transformative approach based in nonviolence wants and needs them to be open to laying down their weapons and choosing new paths - success depends on their defection. If we truly want to abolish policing, we need to do the work of building a world in which that is possible, as abolitionist leaders like Angela Davis and Mariame Kaba emphasise. Sloganeering rarely helps - and frequently hinders - that task.

That's the spirit in which I make this claim: ACAB includes climate COPs.

It is in no way intended to dismiss the genuine commitment of countless thousands of people who have been involved in good faith in the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention of Climate Change) effort to address the climate crisis since 1992 to conclude that the system that effort is embedded within - a capitalist, colonialist, extractivist, undemocratic system of sovereign nation states - makes its goal unachievable and demands that we take a different approach.

And, just as abolishing police means cultivating a world in which communities look after each other, have the skills to de-escalate and manage difficult scenarios, ensure basic needs are met, and help others replicate their successes, replacing climate COPs requires communities to take the lead in building the energy systems, food systems, transport systems and democratic systems we need, and, in so doing, to make the entwined powers of state and fossil capital obsolete.

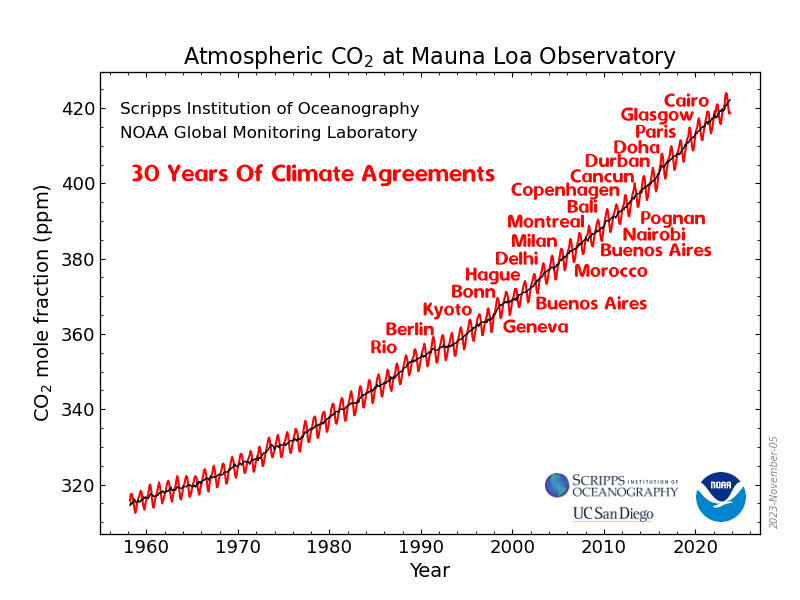

Is it too easy and trite to point to the fact that, after 33 years of intergovernmental negotiation, emissions are still growing? Not just CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere, as this Scripps / NOAA graph shows, but actual emissions are still growing. Indeed, we've produced more emissions in those 33 years since the COP process started than in all of history before. Perhaps they're growing more slowly than they otherwise would have - but only perhaps, as those calculations are based on government promises and reports that are far from trustworthy, as we'll note below.

Is it too easy to emphasise that "[o]ne in every 25 participants at this year's ... summit is a fossil fuel lobbyist", according to analysis by Kick Big Polluters Out? The number has always been atrociously high, but it's still growing. Like the emissions.

It is too easy, because both those factors can be (and are) well recognised and acknowledged by people across the movement while still maintaining faith that we just haven't gotten it done yet.

If, goes the story... if we can build the power to kick the polluters out, and if we can put enough pressure on governments, we can make the system work, so it's worth investing huge proportions of our limited time, energy and money focussing on the COPs. On this basis, organising around the proposed COP in Australia has been taking up tremendous amounts of energy (particularly driven by funders) for years already, despite it still not even being clear if it will happen.*

But we can't kick the polluters out. They - the corporations themselves, and their financial backers, and the global capitalist networks - are entwined with the governments and the bureaucracy. And we can't make the governments act, because democracies are so weak that there is little to no capacity to influence them or make demands of them. See former point on entwining. And we can't make a geopolitics of sovereign nation states work for the general interest - the structures are in direct opposition. We can't make the system work. The system is the problem.

Let's look at a few of these points in turn.

One of the results of the entwining of fossil fuels with government and with global finance is that, from the earliest days of the UNFCCC process, its mechanisms and structures have been thoroughly financialised. Emissions trading, project financing, offsets trading, and creative accounting of all kinds have been embedded deeply into the system. Instead of being last resort options to assist difficult-to-abate industries to take part, they have become the core of the whole approach. And they are "mostly bullshit" as Professor Andrew Macintosh says here.

This is why I suggested that claims about emissions growth slowing are difficult to trust. They rely on government goals and reporting that are based on offsets and accounting tricks like those the Australian government has famously been using for years to pretend to be taking action. Counting carbon in trees that will never grow or will definitely die. Bodging up baselines that nobody can trust. "Avoiding" deforestation that everyone knew wasn't going to happen anyway. There's so much bullshit.

Disentangling the UNFCCC from these non-credible financial and accounting structures now is essentially unthinkable. They are the architecture of the system. Because of this structural reality, success within this system is basically meaningless.

But can't governments just choose to come together and act?

Well, in principle, yes. But how?

Bear in mind that the governments doing the negotiating are not democratic - even the democratic ones. Despite overwhelming popular support globally for climate action, governments are individually and collectively unresponsive. Civil society organisations, and the voices of the people broadly, are excluded from processes domestic and international while fossil fuel corporations and their financiers have not just an open door but co-ownership of the process.

Then there's the problem that the decision-making process demands consensus, but has no clear rules for how that is to be negotiated (the negotiating rules are still in draft after 30+ years, because they could never agree on them).

Now consensus democracy is great! I'm a big believer in it. But, to make it work requires trust, relative power balance, good and open communication, and shared goals. And I've never heard anyone suggest that any of those exist at an intergovernmental level. In particular, economic inequality and geopolitical security concerns make the idea of genuine consensus in that arena ridiculous.

And, of course, instead of building towards trust-based negotiation, we have annual cycles of crisis, with endless brinkmanship, pushing negotiations to the edge, consistently rewarding bad behaviour. The game of chicken currently going on over who will host next year's conference is standard practice. Everyone involved remembers how, 28 years ago in Kyoto, Australia stood up literally at the last second and demanded extra accounting tricks through what became known as "the Australia clause". This model makes for great media stories, with predictable drama, but it means we all invest tremendous amounts of energy and care in a system that is designed to be unworkable.

At the heart of this is the fundamental contradiction running through the liberal ideal of geopolitics that Hannah Arendt (yes, here she is!) identified in The Origins of Totalitarianism 75 years ago: that national sovereignty and universal human rights cannot coexist. Rights are a creature of the liberal state - an invention that depends on the state to grant and enforce them. However, in a global system of sovereign nation states, the granting and enforcing of rights is entirely entangled with the exclusion of non-citizens from those rights, and the inability of other states to intervene in sovereign business behind borders.

Arendt's analysis was primarily concerned with stateless people (which was her personal and very recent experience), for whom "their plight is not that they are not equal before the law, but that no law exists for them" (Origins, Penguin Classics 2017 edition, p387). But this analysis now extends into a broad application of her concept of "rightslessness", where most citizens of most nations are excluded from the capacity to influence decisions that determine our literal capacity to survive. Arendt scholar and Emeritus Professor of Political Theory and International Relations at the University of St Andrews, Patrick Hayden, has written a brilliant and devastating analysis of how, since “the power to exclude [has become] the essence of statist politics”, now “rightslessness is deeply embedded within the logic of the inter-state system".

In this world, continuing to invest in the idea that we can trust or influence the intergovernmental system to protect our interests looks rather problematic.

OK, but what about the idea that, even if we can't get the institutions to act, the process still has a normative impact?

Well, it hasn't even achieved that, has it? Not at a governmental or intergovernmental level. Far from it. After 33 years, we're further behind, if anything.

And what about the argument that "we've got to engage in the UNFCCC, because that's where the power is, that's where the big decisions are being made!"

Is it, though? What big decisions? What power?

I'm thinking about the huge celebrations two years ago when, after years of work, the words "transition away from fossil fuels" were finally included in the text of an agreement for the first time. At COP 28, we finally had some words reflecting the basic reality we've all known for decades. And anyway, those words weren't even binding. And, two years on, they're far from demonstrating success.

I'm thinking about the years of work getting a Green Climate Fund agreed as part of the Paris Agreement. A decade on, and it's systematically underfunded, and constantly gamed.

What power? What big decisions?

We are constantly drawn back to engaging because it feels good, but it very effectively contains our efforts. We think we're contesting power, but we're just playing their game, on their terms. The real decisions are being made elsewhere by people who know they can safely ignore most of what goes on there, or direct efforts into more financialisation and offsetting and misdirection.

Well, ok, but what about the argument that "we simply have got to get it right at the COP, because it's the only option we've got"?

Is it, though?

Why do we have to work through the UN system, if it's so clearly dysfunctional?

I remember, and some of you may, too, back when John Howard was re-elected in 2004, with a Senate majority as well as the House of Reps, the climate and environment movement made a strategic decision to shift focus. We knew there was no chance of real action at a federal level, so we chose to put pressure, for the first time in any serious way, on state and local governments. And we started to make some progress!

The siren song of the highest level in a hierarchical system kept pulling us back, of course. Particularly after Labor was elected, despite constant betrayals, constant signals that they have no intention to phase out fossil fuels. But those years stand as an example that working through federation, at levels closer to the people, can work.

The COPs have always included side events and parallel programs focussing on sub-national leadership, like the Cities for Climate Protection partnership. In part, this was included as a way of keeping the USA involved throughout the Bush years, when there was no chance of their cooperation at a national level.

And, more radically, there have been numerous approaches to "alterglobalisation" over decades, from the World Social Forum to the "global municipalism" of the Fearless Cities Network. They haven't failed. They just struggle to get the ongoing interest of civil society organisations hypnotised by hierarchy and drawn to philanthropic funding that cannot think outside of hierarchy.

Numerous crucial decisions relevant to climate are made by local, municipal, city and other sub-national governments, as well as by communities themselves acting independent of national governments, whether it's on transport, food, energy or nature. Those decisions seem small on their own, but there is simply no reason why they can't be aggregated globally, made cooperatively, learn from each other, support each other, encourage each other, and take the lead globally when governmental and intergovernmental processes have failed.

A globe of sovereign states is no true globe. But, just as communities, acting together in concert for common security, can make the cops obsolete, a globe of communities acting in concert for the climate can make the COPs obsolete.

* We'll know within days. Hence this piece now.

PS: I know I promised that the next piece would be "on the necessity and limits of left populism", but this one somehow got ready first. That one is taking a little longer, but I intend to get it done this week. If you've been forwarded this by email, or found it online, please subscribe to make sure you get that next one in your inbox! And please pass this on to others who might find it interesting. I write because it helps me think things through, but it's good to know people are reading it and finding it useful.